Introduction: Ozu Portrayal of Post War Japan

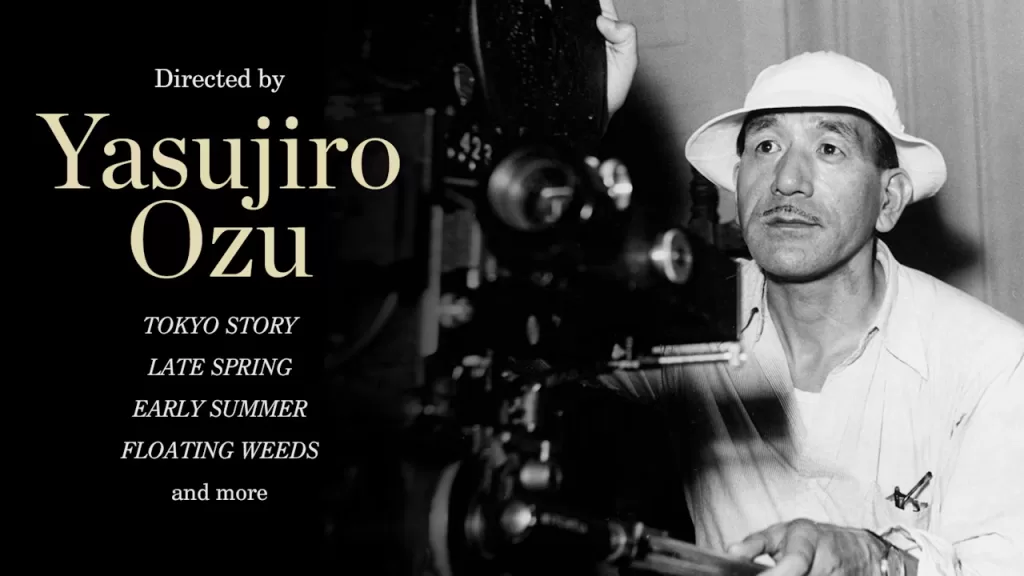

Yasujiro Ozu is often hailed as one of the most significant directors in the history of cinema. His films provide an intimate portrait of Japan’s post-war landscape, especially focusing on the evolving nature of family dynamics amidst the social and cultural transformations of the time. Through his films, Ozu profoundly explores the complex relationships between generations and how the tension between tradition and modernity impacted Japanese families. His work not only captures the nuances of personal relationships but also provides a window into the broader societal changes that reshaped Japan following its defeat in World War II.

The Social Context of Post-War Japan

The defeat in World War II left Japan in a state of devastation, both physically and emotionally. The country was under U.S. occupation from 1945 to 1952, which saw a significant restructuring of its political, social, and economic systems. Westernization played a significant role during this period, as Japan was encouraged to adopt democratic values, a market economy, and Western cultural norms. Simultaneously, Japan’s centuries-old traditions faced tremendous pressure as urbanization and industrialization began to transform the nation. This societal upheaval created a cultural tension between maintaining traditional Japanese customs and adapting to the modern world.

For Ozu, this tension between old and new, particularly within the family unit, became the crux of many of his films. Through everyday family life, Ozu illuminated the subtle but profound emotional shifts that occurred as Japan transitioned from a feudal society to a modern, industrialized nation. The family—often seen as the backbone of Japanese culture—became the lens through which Ozu examined this transformation, capturing the struggles, sacrifices, and adaptations necessary to navigate these turbulent times.

Family as the Core of Ozu’s Storytelling

At the heart of Yasujiro Ozu’s cinema lies the family unit, which serves as both a narrative device and a reflection of broader societal issues. Ozu was particularly concerned with generational conflict—the relationship between parents, who are often depicted as adhering to traditional Japanese values, and children, who are caught between cultural expectations and the lure of modernity.

In Ozu’s most famous film, Tokyo Story (1953), the aging parents of the Hirayama family travel to Tokyo to visit their children. The visit exposes the emotional distance between the elderly parents and their children, who are preoccupied with their busy, modern lives. The children’s indifference toward their parents’ needs highlights the breakdown of traditional familial values in a society undergoing rapid change. This theme of neglect and disconnection is not only a personal matter but also a cultural critique of post-war Japan, where younger generations increasingly embraced Western ideals of individualism and self-reliance.

In films such as Late Spring (1949) and Early Summer (1951), Ozu explores the role of women within the family. These films portray daughters who must choose between fulfilling their filial obligations and pursuing their own happiness, often in the form of marriage. The pressure to marry and continue the family line was deeply embedded in Japan’s traditional culture. Yet, Ozu’s characters often challenge these roles, highlighting the conflict between the duties of the past and the desires of a more modern, liberated future. In this way, Ozu uses family dynamics to engage with the societal shifts in post-war Japan, questioning the future of traditional values in a rapidly changing world.

The Impact of Westernization on Family Dynamics

In the aftermath of the war, Japan was deeply influenced by Western ideals—especially those promoted by the United States. This influence manifested in the growing prominence of individualism and materialism, which were often at odds with the collectivist and family-oriented ideals that had long defined Japanese society. Ozu’s films often explore how this Westernization creates tension within families, as older generations struggle to preserve traditional values while younger generations gravitate toward more modern, often Westernized, lifestyles.

In Early Spring (1956), Ozu delves into the complexities of a young office worker’s life, caught between the demands of his traditional family and his own aspirations for a modern, more self-indulgent life. The character’s relationship with his wife, who is also caught between duty and personal fulfillment, underscores the pressures of living in a society where materialism and personal autonomy are becoming increasingly normalized. Ozu’s films thus reflect the growing divide between those who wish to maintain the old ways and those who embrace the new order emerging in post-war Japan.

Ozu’s Cinematic Techniques and Family Narratives

Ozu’s filmmaking style is integral to his storytelling. His use of low-angle shots, often referred to as “tatami shots” (since they mimic the viewpoint of a person sitting on a tatami mat), creates a sense of intimacy and stillness, inviting the viewer to become deeply involved in the emotional landscape of the characters. This static composition contrasts with the chaotic, fast-moving world that Ozu’s characters inhabit, allowing his films to reflect the quiet but profound emotional currents of everyday life.

The careful attention to details in Ozu’s films—from the modest rituals of daily life to the subtle shifts in a character’s demeanor—reflects the emotional depth of his storytelling. In An Autumn Afternoon (1962), Ozu’s final film, this attention to detail is apparent in the portrayal of an elderly man’s relationship with his daughter. The film reflects on themes of loss, change, and the passage of time—key concerns in post-war Japan. The understated yet deeply emotional nature of the film reveals Ozu’s ability to capture the complexities of human relationships within the context of a rapidly changing society.

The Role of Gender in Ozu’s Post-War Japan

One of the notable aspects of Ozu’s post-war films is his nuanced portrayal of gender roles, particularly the roles of women. In many of Ozu’s works, women are depicted as navigating the space between traditional family obligations and the opportunity for personal autonomy. Ozu’s female protagonists often struggle with the pressures placed on them by family and society, as seen in Late Spring (1949), where the protagonist Noriko is expected to marry, not because she wants to, but because her father’s happiness depends on it.

In films like Tokyo Story, Ozu explores how post-war society impacted women’s roles in the family. The generational divide is particularly visible in the role of the mother, who is portrayed as embodying traditional values, while her children increasingly reject these norms. The struggle of Ozu’s female characters reflects broader societal issues in post-war Japan, where women’s roles were being redefined, and the very nature of family obligations was coming into question.

The Post-War Generation and the Impact on Youth

The youth of post-war Japan are a vital part of Ozu’s cinematic exploration. The younger generation, portrayed in Ozu’s films as somewhat detached from the traditions of the past, is often seen as the harbinger of change. In The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952), Ozu delves into the story of a couple where the wife is expected to fulfill traditional roles as a dutiful wife, yet her desire for freedom and personal fulfillment underscores the clash between the older and younger generations. Ozu’s depiction of youth serves as a reflection of the changing social order and the increasingly influential role of individualism in post-war Japan.

A Timeline of Ozu’s Exploration of Post-War Japan Through Family

- 1949: Late Spring – This film captures the generational conflict between a widowed father and his daughter, highlighting societal expectations of marriage and duty.

- 1951: Early Summer – Continuing the exploration of family dynamics, this film delves into the changing roles of women and the growing generational divide.

- 1953: Tokyo Story – Ozu’s masterpiece, depicting the emotional distance between elderly parents and their children, who are caught up in modernity’s demands.

- 1956: Early Spring – Ozu examines the impact of Westernization on personal lives, focusing on a young man torn between tradition and the pursuit of personal satisfaction.

- 1962: An Autumn Afternoon – Ozu’s final film explores the themes of aging, generational conflict, and the reconciliation of tradition with modernity.

Experts Opinions on Ozu’s Depiction of Post-War Japan

David Bordwell, a leading film theorist, has praised Ozu’s ability to reflect the cultural tension of post-war Japan, commenting that Ozu’s static camera and focus on familial relationships were essential in conveying the “emotional weight” of the generational divide. Bordwell writes, “Ozu’s films are masterful in depicting how familial expectations collide with the pressures of modernity. His quiet, contemplative approach allows for a deep exploration of societal transformation.”

Donald Richie, an authority on Japanese cinema, highlights Ozu’s ability to reflect the contradictions within post-war Japan. He asserts, “Ozu’s films capture the emotional essence of the post-war period, revealing the complexities of a nation struggling to preserve its traditions while embracing the future.”

Conclusion: Ozu’s Legacy and the Transformation of Post-War Japan

Yasujiro Ozu’s films remain an invaluable resource for understanding the social and cultural transformation of post-war Japan. His insightful exploration of family dynamics, tradition, and the generational tensions at play during a time of rapid change reveals a deep empathy for the personal and societal challenges faced by the Japanese people. Through Ozu’s lens, we witness the evolving nature of family life, the effects of Westernization, and the tension between modernity and tradition—all set against the backdrop of a Japan in transition. Ozu’s cinematic legacy continues to resonate, offering timeless insights into the complexities of family, culture, and change.

📚 Take Your Trading And Financial Skills to the Next Level!

If you enjoyed this post, dive deeper with our Profitable Trader Series—a step-by-step guide to mastering the stock market.

- Stock Market 101: Profits with Candlesticks

- Stock Market 201: Profits with Chart Patterns

- Stock Market 301: Advanced Trade Sheets

Start your journey now!

👉 Explore the Series Here

For Regular News and Updates Follow – Sentinel eGazette

FAQs

Q1: How does Ozu’s portrayal of family reflect post-war societal changes in Japan?

A1: Ozu’s films depict generational conflict within the family, highlighting the shift from traditional Japanese values to Western influences in post-war society. Characters often struggle with balancing old obligations with modern desires, capturing the emotional tension of a transforming Japan.

Q2: How did Westernization impact the family unit in Ozu’s post-war Japan films?

A2: Ozu’s films show the growing tension between individualism and collectivism. As Western values began to permeate Japanese society, younger generations drifted from traditional family structures, causing emotional and familial strain, which Ozu portrays with emotional depth.

Q3: In which film does Ozu explore the generational divide most effectively?

A3: Tokyo Story (1953) is Ozu’s most well-known film exploring the generational divide. It portrays the emotional distance between elderly parents and their children, shedding light on the societal pressures of modernization and familial obligations.

Q4: What is the role of women in Ozu’s films post-WWII?

A4: Women in Ozu’s films are often seen negotiating the balance between traditional family roles and newfound freedoms. Ozu examines their struggles to reconcile marriage, duty, and personal fulfillment amid a society shifting towards modernity.

Q5: How did Ozu’s filmmaking style contribute to his portrayal of post-war Japan?

A5: Ozu’s static, low-angle shots create intimacy, giving viewers a window into the emotional intricacies of family life. This calm yet poignant style allows Ozu to deeply explore the personal and societal tensions that arose in post-war Japan.