Introduction: Edo Period Administrative Structure

The Edo Period (1603-1868) marked a significant chapter in Japan’s history, characterized by long-lasting political stability, economic growth, and isolation from the outside world. This period of over 250 years was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, and its success was in large part due to its well-organized and complex administrative structure. This structure, while ensuring stability and peace, was also instrumental in shaping the nation’s socio-political landscape. In this expanded and elaborated article, we will explore the intricacies of the Edo administrative system, with deeper insights, expert opinions, and a detailed timeline of key events.

Understanding the Tokugawa Shogunate’s Role in Governance

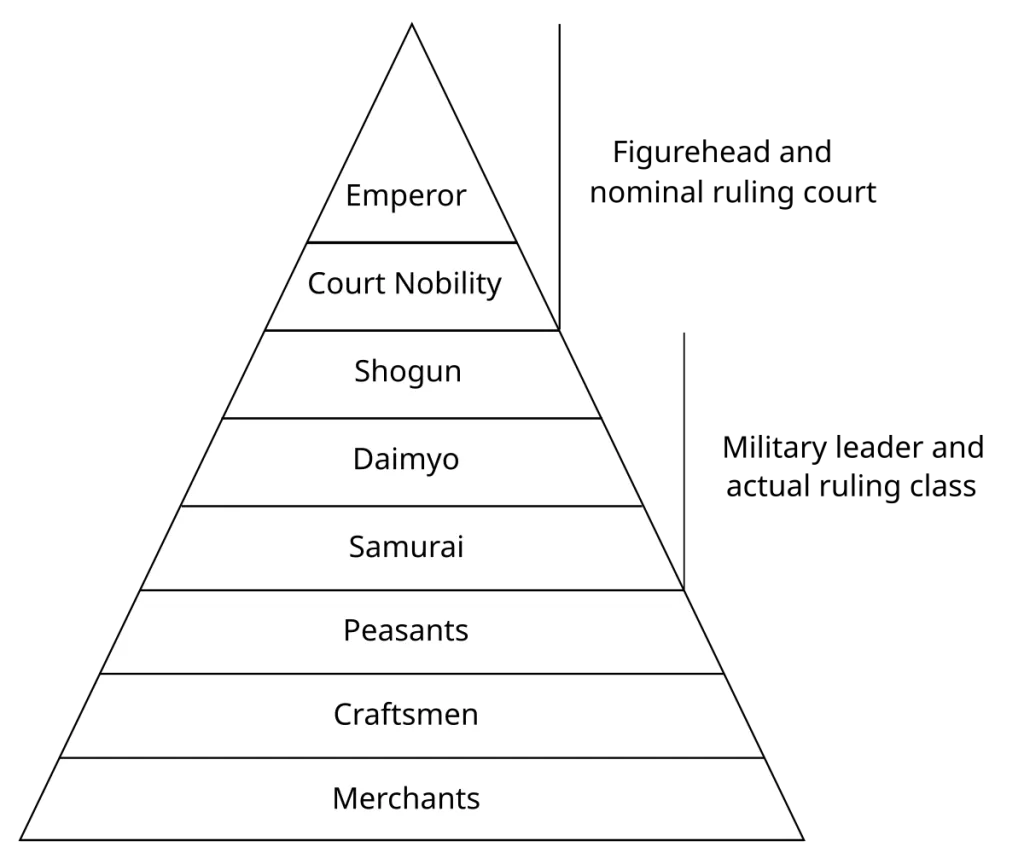

At the center of the Edo administrative system was the Shogun, the head of the Tokugawa family and the de facto ruler of Japan. The Shogunate established its rule in 1603 under Tokugawa Ieyasu, who secured his dominance after the Battle of Sekigahara. The Shogun wielded vast power over military, political, and economic affairs, though the structure was designed to ensure control was spread out among various officials, creating a system that was both decentralized and controlled.

The Shogun was the supreme ruler, responsible for overseeing Japan’s military and foreign relations. He issued decrees, made treaties, and governed the Bakufu (the Shogunate government). However, despite his immense authority, the Shogun could not rule alone. The position was hereditary, passed down within the Tokugawa family, ensuring consistent leadership for more than two centuries. But it was not just the Shogun who wielded power — his administration included various layers of officials and bureaucrats.

The Role of the Daimyo and the Han System

The Tokugawa Shogunate implemented the han system, which divided Japan into multiple domains, each governed by a Daimyo (feudal lord). This system played a critical role in ensuring loyalty from regional lords while also allowing them to manage their own territories.

The Daimyo were granted control over their respective domains in exchange for loyalty and military service to the Shogunate. This arrangement helped prevent the rise of independent regional powers and ensured that the Shogunate maintained control over Japan’s various territories. The han system functioned as a regional feudal system where each Daimyo was responsible for governance, law enforcement, and tax collection within their domain.

An essential feature of the system was the sankin-kotai, or the “alternate attendance” policy, which required Daimyo to spend alternating years in Edo, the Shogunate capital, to keep them under close surveillance. This prevented rebellion and ensured that the Daimyo could not accumulate too much power in their home regions. If they refused to comply, their domain could be confiscated by the Shogunate. This system also placed heavy financial burdens on the Daimyo, as they had to maintain two residences—one in their own domain and one in Edo.

The Samurai Class and its Role in Administration

The Samurai class was integral to the Edo administrative system, serving not only as warriors but also as civil servants. Samurai were expected to adhere to the Bushido code, which emphasized loyalty, honor, and martial skill. But beyond their military role, the Samurai also played crucial roles in governance, with many serving in bureaucratic and administrative positions.

The Samurai held official positions within the Bakufu and acted as government officials overseeing everything from finance to law enforcement. They were tasked with collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and ensuring the smooth functioning of the administrative machinery. Samurai administrators could be found managing the local government, overseeing the land and its resources, or even acting as judges in the local courts.

This dual role of Samurai as both military leaders and administrators helped to integrate the warrior class into the social and political fabric of the era. The Samurai were the backbone of the Bakufu and were the key players in maintaining the stability of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

The Bakufu: The Government Machinery of the Tokugawa Shogunate

The central government of the Tokugawa Shogunate was known as the Bakufu, and it was responsible for overseeing and implementing the Shogunate’s policies throughout Japan. The Bakufu was structured like a modern-day bureaucracy, with specific departments and officials responsible for different areas of governance.

One of the most critical positions in the Bakufu was the roju, the senior advisors who helped the Shogun in decision-making. The roju were responsible for high-level political and military matters, advising the Shogun and helping to shape policies. Another important position was that of the bugyo, who were commissioners responsible for the enforcement of laws, management of cities, and even military matters in certain domains.

Beneath these senior officials, there were other positions, such as the Jisha-bugyo, who managed religious and temple affairs, and the Kanjo-bugyo, who handled finance. This hierarchical system ensured that Japan was governed efficiently from the central government, while still respecting the autonomy of local domains.

The Role of the Townspeople and the Peasantry

The Townspeople (or Chōnin) and the Peasants (or Hinin) were the backbone of Japan’s economy during the Edo Period. While the Samurai class held political power, it was the peasants and townspeople who kept the country running on a day-to-day basis.

Peasants were the primary producers of rice, which was the country’s main commodity and a measure of wealth. They lived in rural areas and were bound to their land, subject to heavy taxation by both the Shogunate and the Daimyo. In return for their labor, they received limited rights but were subject to numerous restrictions, including the inability to own land freely or change their place of residence without government approval.

On the other hand, the Townspeople formed the merchant class that grew during the Edo period. While they had no direct political power, their contributions to trade, craft, and the economy were crucial to the success of the Bakufu system. Merchants, artisans, and traders helped establish a vibrant urban culture, particularly in cities like Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka.

Timeline of Key Events in the Edo Administrative Structure

- 1603: Tokugawa Ieyasu is granted the title of Shogun, marking the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Edo Period.

- 1615: The Sankin-kotai system is formalized, requiring Daimyo to spend alternating years in Edo.

- 1635: The Closed Country Edict (Sakoku) is issued, marking the start of Japan’s isolationist foreign policy.

- 1707: The Great Famine of Edo (also known as the Tenmei famine) devastates rural areas, leading to increased taxation and unrest among peasants.

- 1853: Commodore Matthew Perry forces Japan to open its ports, ending over 200 years of isolation.

- 1867: The Meiji Restoration begins, marking the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Expert Opinions on the Edo Period Administrative System

Experts in Japanese history have noted that the Edo administrative system, despite its rigidity, played an essential role in maintaining peace and order during the era. According to Dr. Kazuhiro Nakamura, a Professor of Japanese History at the University of Tokyo:

“The Edo system’s strength was in its ability to maintain a delicate balance between central control and regional autonomy. This balance kept regional lords loyal to the Shogunate, while allowing them enough freedom to govern their territories effectively.”

Prof. Yuki Tanaka, a prominent scholar of Japanese feudal systems, adds:

“While the system was designed to prevent rebellion, it also had a dual purpose of encouraging economic growth and promoting a sense of stability, especially in cities like Edo. This is why the Tokugawa Shogunate is often credited with creating a peaceful and prosperous era in Japanese history.”

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Edo Administrative System

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s administrative system was one of the most well-structured and efficient in history. By balancing centralized control with regional autonomy, and creating a strong bureaucratic system, the Edo Period lasted for over two centuries. While the system was not without its flaws, including its eventual inability to adapt to changing circumstances, it ensured that Japan remained stable and largely isolated from the outside world until the mid-19th century. This remarkable administrative framework left a lasting impact on Japanese governance and continues to influence the country’s political and social systems today.

📚 Take Your Trading And Financial Skills to the Next Level!

If you enjoyed this post, dive deeper with our Profitable Trader Series—a step-by-step guide to mastering the stock market.

- Stock Market 101: Profits with Candlesticks

- Stock Market 201: Profits with Chart Patterns

- Stock Market 301: Advanced Trade Sheets

Start your journey now!

👉 Explore the Series Here

For Regular News and Updates Follow – Sentinel eGazette

FAQs:

Q1: What were the major changes in governance during the Edo Period?

A1: The Edo Period saw significant administrative reforms, including the implementation of the Sankin-kotai system, which required Daimyo to spend alternating years in Edo. This ensured the loyalty of regional lords and limited their power in their respective domains. Additionally, the establishment of a centralized bureaucracy under the Shogunate streamlined governance across Japan.

Q2: How did the Sankin-kotai system affect local economies during the Edo Period?

A2: The Sankin-kotai system placed a financial burden on the Daimyo, as they were required to maintain two residences. This led to a flourishing economy in Edo, with merchants benefiting from the constant flow of people and resources, though it also contributed to economic strain in rural domains where taxes were increased to support the system.

Q3: What role did the Samurai class play in the administration during the Edo Period?

A3: While the Samurai were traditionally warriors, during the Edo Period, many Samurai served as government officials. They managed tax collection, law enforcement, and civil service positions. Their dual role as both soldiers and administrators contributed to the stability of the Tokugawa Bakufu.

Q4: Why did the Tokugawa Shogunate focus on internal stability rather than external relations?

A4: The Tokugawa Shogunate prioritized internal stability to avoid the conflicts that plagued Japan during the previous Sengoku Period. The isolationist policy, known as Sakoku, which lasted for over 200 years, allowed Japan to maintain peace by controlling foreign influence and limiting external threats.

Q5: What led to the downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868?

A5: The Meiji Restoration in 1868 marked the downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The external pressure from Western countries, particularly after Commodore Matthew Perry’s arrival in 1853, forced Japan to open its borders. Coupled with internal dissatisfaction, the Shogunate was unable to adapt to these rapid changes, leading to the collapse of feudal rule.